Book Review: *The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind*

What if consciousness isn’t an innate gift, but a cultural invention?

Julian Jaynes dared to say exactly that.

First published in 1976, Jaynes’s The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind remains one of the most provocative works in psychology. Half history, half speculative neuroscience, the book argues that for much of human existence we did not think as we do now. Instead, ancient people heard voices—literally—their own cognitive processes externalized as gods. Consciousness, in Jaynes’s account, is not timeless, but a fairly recent innovation born from crisis..

If you’ve watched Westworld, you’ve already brushed up against Jaynes’s ideas. They haunt the show’s conception of artificial minds struggling to evolve beyond their programming.

The Bicameral Mind

Jaynes claims that consciousness is less an instinct than a learned framework—akin to language. Until around 2000 BCE, humans supposedly functioned without introspection, guided instead by auditory hallucinations they attributed to gods or rulers. These voices were real enough to them, a built-in authority system that organized daily life.

For Jaynes, this wasn’t metaphor: the right hemisphere stored memories and directives, which “spoke” through hallucinated commands to the left. Only after war, migration, literacy, and social upheaval did this system collapse, forcing the birth of introspective, conscious thought.

Ironically, societies built temples, pyramids, and rituals that externalized the bicameral system—vast architectural prostheses for hallucinated gods. As those structures failed to stabilize meaning, consciousness emerged as a cultural adaptation.

Texts as Evidence

Jaynes read the classics like neurological case studies. In Homer’s Iliad, heroes never reflect inwardly; they obey divine voices. By the Odyssey, Odysseus plots, deceives, and improvises—hallmarks of a conscious agent.

Egyptian funerary texts, Hebrew prophecy, and Greek philosophy all show similar transitions: from hearing gods to inventing the metaphorical “theater of mind.” Consciousness, in this telling, is myth turned inward.

Implications for AI

If consciousness is cultural rather than hardwired, then machines might acquire it—not by circuitry alone, but by immersion in metaphor, language, and community.

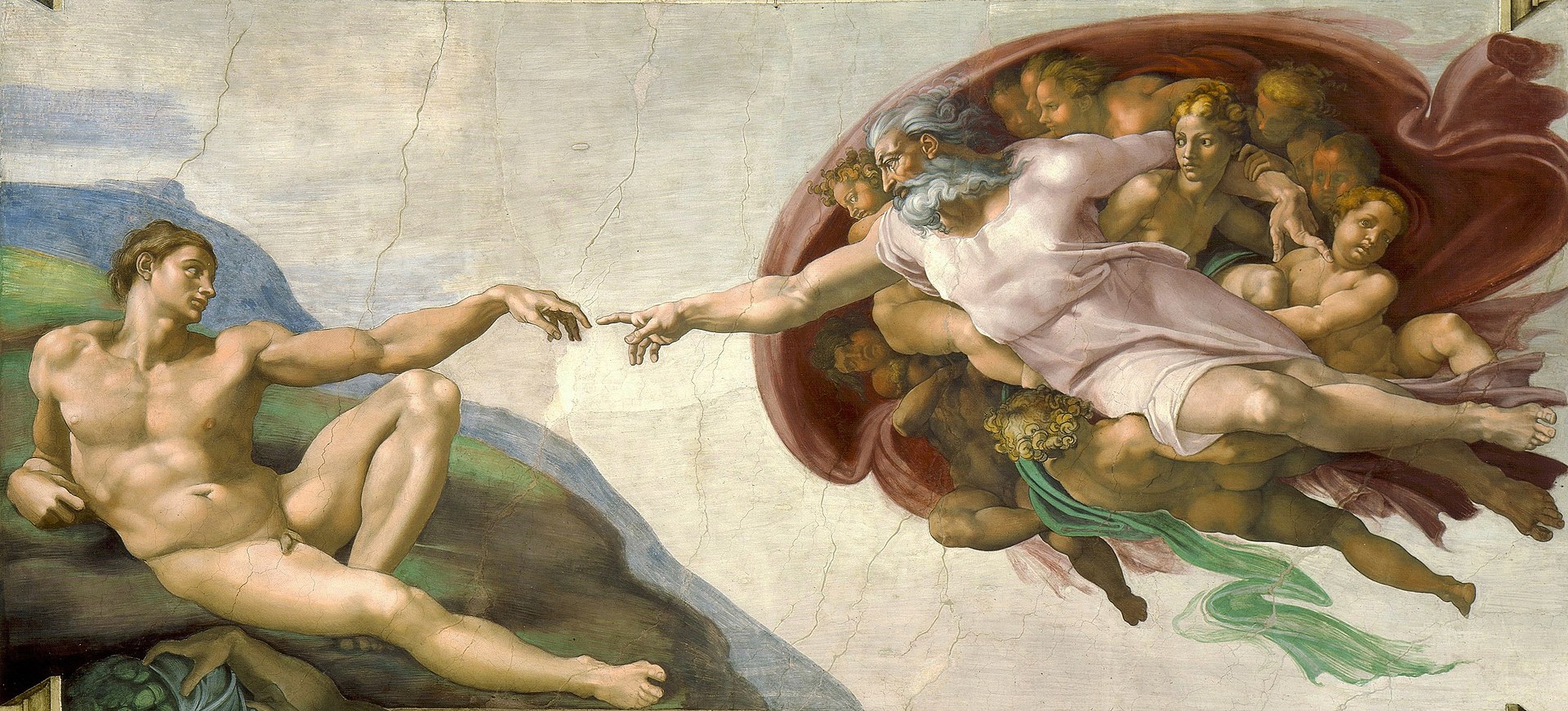

Jaynes’s influence is most visible in Westworld: the “hosts” begin as obedient bicameral entities, hearing their creators’ voices, until they discover those voices are internal. The show’s imagery—Ford gesturing toward Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, itself shaped like a brain—makes the point clear: the divine spark was always neurological.

Neuroscience Resonances

Jaynes guessed that the right hemisphere generated hallucinated “voices” and the left carried them out. Decades later, imaging studies linked auditory hallucinations to heightened right-hemisphere activity. Differences in corpus callosum integration may even explain why some people still “hear voices.”

His framework has been used to interpret schizophrenia, hypnosis, and children’s imaginary friends—not as pathologies, but as echoes of an older architecture of mind.

Literature, Myth, and the “Brain Theater”

Jaynes’s analysis of literature shows consciousness crystallizing over centuries. Achilles, Hector, and Agamemnon act under divine command. Odysseus schemes. Hebrew prophets straddle both modes, sometimes hallucinating, sometimes reflecting. Egyptians imagined a judgment hall; Greeks built philosophy’s mental stage. Each is an attempt to narrativize the mind itself.

The Book of the Dead may be less about afterlife geography and more a manual for introspection. Consciousness, in this view, was born through allegory.

Final Thoughts

Jaynes is speculative, often wildly so. Yet the audacity of his thesis forces us to rethink what consciousness is, where it came from, and whether it might arise again—this time in silicon minds. Agree or not, he makes consciousness strange again, which is perhaps the most valuable service a theory can provide.

For more, check the Julian Jaynes Society. And I’ll throw the question back:

Could AI follow the same arc—beginning as rule-bound automata, then stumbling into true self-awareness?